European novel food approvals drag on for years, new study warns, putting innovation at risk

A new study has revealed that companies hoping to launch novel foods in the European Union face average wait times of more than two and a half years, highlighting how complex regulatory hurdles are delaying innovation and potentially undermining Europe’s ambitions for sustainable food systems.

The analysis, published this week in npj Science of Food, examined the timelines of 292 applications submitted to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) under Regulation (EU) 2015/2283, which governs how new food ingredients are evaluated for safety. Researchers found that the entire process – from submission of a novel food dossier to publication of EFSA’s scientific opinion – takes an average of 2.56 years, or around 31 months. For some companies, the wait was as long as six years.

“The lengthy administrative procedures, despite a high rate of positive EFSA opinions, suggest that the current framework may be excessively burdensome,” wrote authors Jérôme Le Bloch, Marie Rouault, Cédric Langhi, Malorie Hignard, Victoria Iriantsoa, and Olivier Michelet. “Such inefficiencies could discourage applicants from engaging with the regulatory process and risk undermining the innovation-friendly environment that the European Union aims to promote.”

Novel foods, defined as any food not consumed to a significant degree in the EU before 15 May 1997, include categories such as new plant proteins, fungal biomasses, cellular agriculture products like cultivated meat, and ingredients derived from agri-food waste. These innovations are widely viewed as crucial to reducing the environmental impacts of food production. Studies have shown that substituting traditional animal proteins with novel foods could cut global warming potential, water use, and land use by over 80%. Yet, despite their promise, many of these products remain unavailable in Europe because they are still awaiting regulatory approval.

The new research is the first comprehensive analysis quantifying how long each stage of the EU’s approval process actually takes. According to the study, simply getting an application validated – that is, confirming the dossier is complete enough for EFSA to start its scientific assessment – takes an average of 299 days. That step alone can range from as little as 20 days to as long as 4.5 years.

Once EFSA starts evaluating the safety of a novel food, the process averages about 629 days, or more than 20 months. Although European regulations call for EFSA to issue its opinion within nine months, the study found this deadline was exceeded in more than a quarter of all completed evaluations. On average, those delays added an extra 156 days to the timeline, with some running nearly three years over the target.

A major cause of these overruns is the frequent back-and-forth between EFSA and applicants. The agency typically issues about 2.7 requests for additional information per application, covering topics such as production methods, compositional data, or toxicological testing. Companies take an average of 130 days to respond to each request, collectively accounting for nearly half of the time spent in EFSA’s evaluation phase.

“The time taken by applicants to answer EFSA requests represents 47% of the total evaluation time, while EFSA evaluation represents only 53%,” the researchers reported.

After EFSA adopts its opinion, there’s still a wait of around 48 days before the assessment is formally published. Overall, from submission to publication, the full process averages nearly 937 days. Despite these hurdles, the approval rate is high: EFSA gave a positive opinion to about 87% of published applications.

Yet while the majority of novel food applications succeed, the hurdles are considerable. Thirty applications were outright rejected because they failed to comply with Europe’s Transparency Regulation, which has been in force since March 2021. That law requires companies to notify EFSA of any scientific studies before submitting their applications. Missing this step can result in an automatic rejection, adding risk and uncertainty for businesses attempting to navigate the system.

Rejections on these grounds took an average of 297 days from EFSA receiving the application to issuing the decision. Although the researchers noted a slight decrease in rejection times in recent years, the legal and procedural complexity remains a significant barrier for food innovators.

Importantly, EFSA’s involvement in the novel food process is not technically mandatory under EU law. Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 states that the European Commission should request EFSA’s opinion only if a scientific assessment is deemed necessary. However, in practice, the Commission refers virtually all applications to EFSA, even in cases where products have already been assessed elsewhere or involve only minor changes.

“Implementing more robust upstream risk assessments could streamline the process by reducing the number of dossiers sent to EFSA,” the authors wrote. “Such measures would help reduce approval timelines and facilitate broader access to safe, innovative food products across the European market.”

Long approval times pose more than a regulatory inconvenience. They could undermine Europe’s broader sustainability goals, including those set out in the Farm to Fork Strategy, part of the European Green Deal. Sustainable alternatives such as plant-based proteins, fungal biomass, and cellular agriculture products have already won approval in other regions, but remain largely inaccessible in the EU while applications remain pending.

The delay also carries significant risks for the European food industry’s competitiveness. Start-ups and small businesses developing novel ingredients often rely on rapid market access to secure investment and generate revenue. Lengthy regulatory timelines can strain finances, discourage entrepreneurs, and even drive some innovators out of the market altogether.

The authors of the new study argue that the European system could remain rigorous and science-based while improving efficiency. Clearer guidance for applicants, higher dossier quality, and more structured pre-submission dialogue could help avoid time-consuming additional data requests. Equally, a more selective approach to which applications require EFSA’s full scientific scrutiny could free up resources for truly novel or complex evaluations.

“Our findings underscore the need for a critical reassessment of the procedural design of NF evaluations in the EU,” the researchers concluded. “Balancing scientific rigor with regulatory efficiency is essential to maintaining food safety without impeding innovation.”

As Europe looks to build more sustainable, resilient food systems, the authors warn that further delays in approving novel foods could hamper progress and leave consumers waiting for safe, innovative products already available elsewhere.

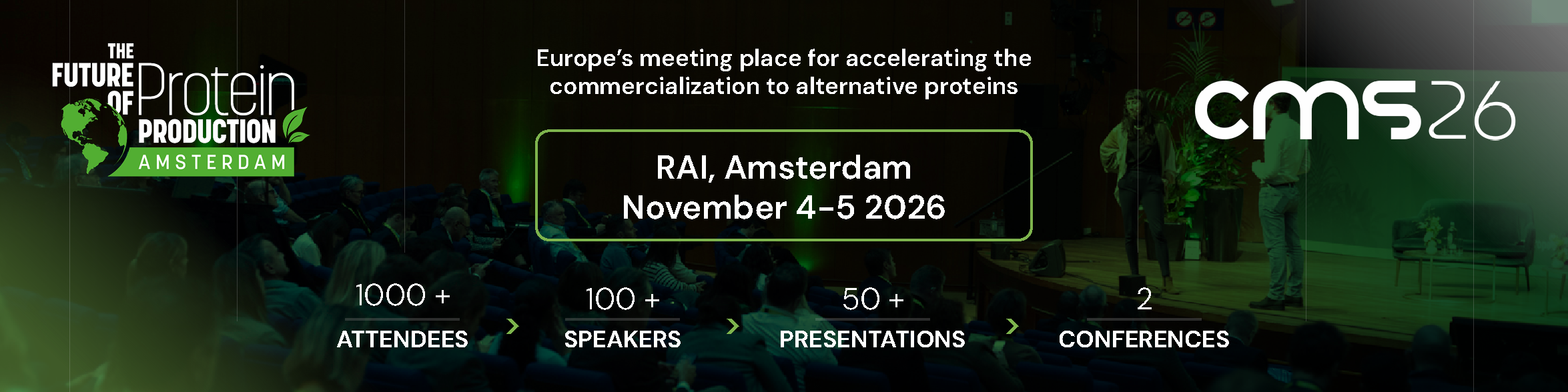

If you have any questions or would like to get in touch with us, please email info@futureofproteinproduction.com

.png)

-25.jpg)