Merck, Vow, MilliporeSigma and Solar Foods lift the lid on keeping alternative proteins safe

What happens if the foods that promise to fix the climate lose consumers’ trust on safety? That question sat at the heart of Protein Production Technology International’s latest webinar, What’s At Stake When Sustainable Food Isn’t Safe?, held in partnership with the Life Science business of Merck, which operates as MilliporeSigma in the USA and Canada.

Across an hour of discussion, speakers from Merck, Solar Foods, MilliporeSigma and cultured meat producer Vow made a clear case that alternative proteins would only scale if safety culture, environmental monitoring and smart regulation kept pace with scientific innovation.

For Merck’s Global Product Manager Innovation F&B IPLCM, Sam Santiago, the fundamentals of food safety did not change just because the ingredients were new. He stressed that every food manufacturer, whether working on traditional products or alternative proteins, needed to test three things: raw materials, finished products and the production environment.

His focus was firmly on environmental monitoring, which he argued remained underappreciated. Air, surfaces, personnel and water all had to be checked, along with pathogens such as salmonella, E. coli and listeria, supported by a clear program of sampling, trending and corrective action when problems appeared. Chemical residues from disinfectants, basic cleanliness checks with ATP tests and, where relevant, allergen monitoring all formed part of that picture.

Santiago described the alternative protein sector as being in its infancy, warning that a single recall could have outsized consequences. “If there’s a product recall on salad in the newspaper today, people might stop eating salad for a day, a week, maybe a month,” he said. “But if there’s a big news story that an alternative protein brand has a salmonella issue and a recall is required, that will have a very serious impact on the entire alternative protein market.”

While his team often borrowed tools and ideas from pharmaceutical manufacturing, he drew an important distinction between the two sectors. In pharma, sterility expectations were effectively zero tolerance, while in food there was an acceptable range of microorganisms and different risk profiles. Trying to apply pharmaceutical limits wholesale to food, he suggested, could drive unnecessary costs without necessarily improving safety.

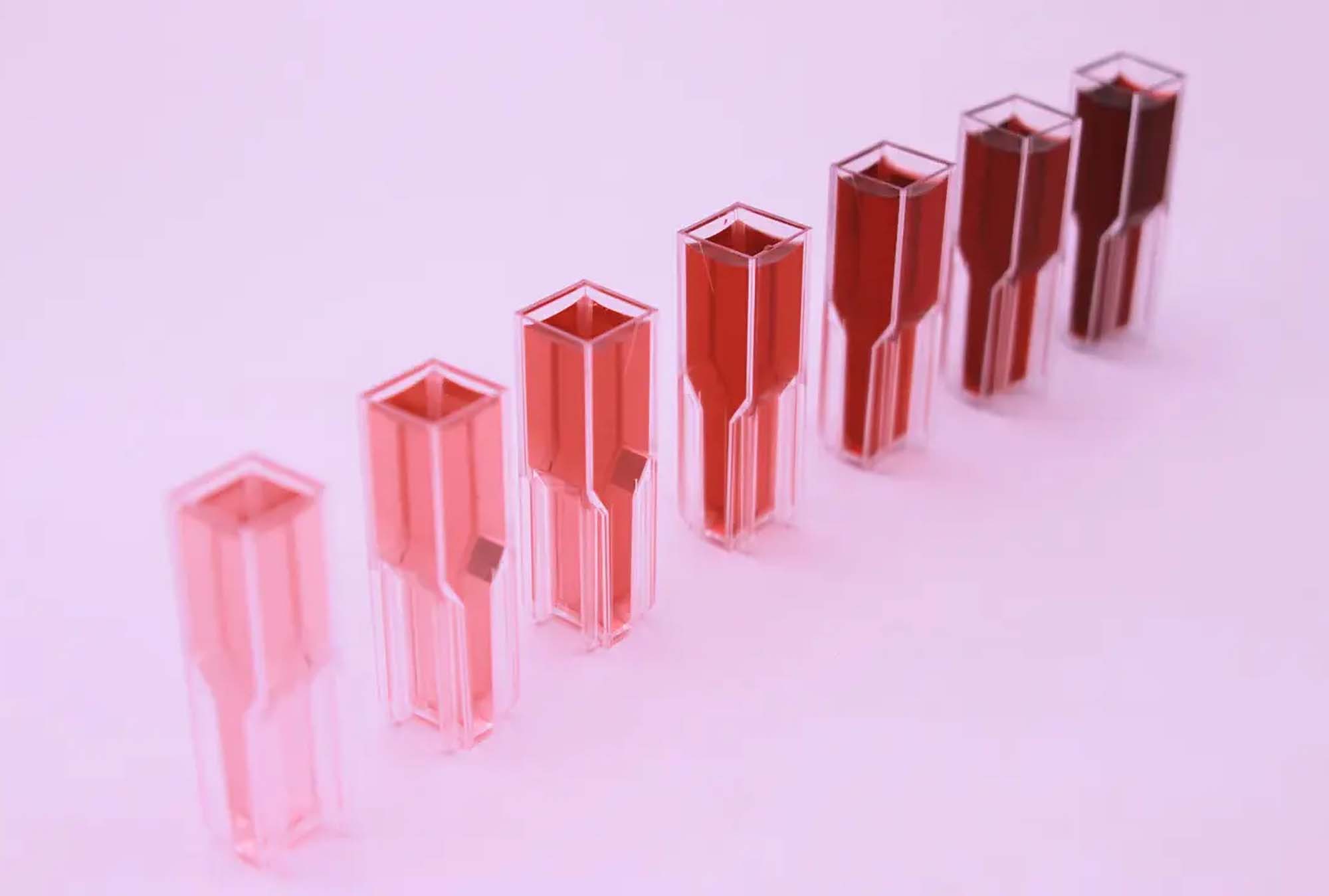

If Santiago outlined the principles, Solar Foods’ Head of Global Regulatory Affairs, Ida Aabrandt Søndergaard, showed what they looked like inside a radically different production model. Solar Foods produces Solein, a yellow, umami-rich bacterial biomass protein powder grown using gas fermentation. The company discovered its microbe in Finnish nature and fed it with three gases, including CO₂ from the air plus hydrogen and oxygen produced using renewable power and water, along with minerals.

Because the microbe had no history of consumption, Solar Foods had to build its safety case from scratch. Søndergaard said the company had conducted toxicological and other studies to show Solein was safe to eat, then turned to the challenge of making sure it was produced safely at scale. As a small startup, that meant running regulatory work, production build-out, hazard planning and quality systems in parallel.

She argued that the smartest way for startups to embed safety was to recognize their blind spots early and bring in the right expertise. “Most startups and small companies are built by very entrepreneurial, scientific people who have these crazy, lovely brains that create amazing products,” she said. “But it’s also important to know your blind spots and to bring in people who can help you. That can be consultants or in-house expertise, and I think a combination of both is the perfect way to go.”

MilliporeSigma Regulatory Affairs SME for Life Science and Public Health, Sarah (Sally) Powell-Price, picked up that theme, urging companies to develop relationships with regulators before any problems arose. She pointed to trade associations in the US and collaborative work with FDA and USDA around cultured meat oversight as examples of how proactive engagement could pay off.

Global food safety certifications such as FSSC 22000, SQF or BRC also offered a practical route to building internal competence, especially for teams coming from biotech or other non-food sectors. These frameworks, she said, not only trained personnel but connected startups with a wider ecosystem of consultants and auditors.

Powell-Price warned, however, that chasing multiple markets too quickly could strain those systems. In the US, she noted, the average product recall cost more than US$10 million, even at small scale, once product loss and reputational damage were taken into account. With fragmented state and federal rules, and other regions such as Brazil developing their own novel protein regulations, she argued that strong local knowledge and trusted partners on the ground were essential.

From the cultured meat side, Vow’s Naya McCartney offered a candid view of how safety thinking had evolved inside one of the sector’s most closely watched companies. Vow grew animal cells in bioreactors up to 20,000 liters, using a proprietary, fetal bovine serum-free and antibiotic-free growth media, then harvested those cells to create meat-like products for chefs and restaurants.

McCartney said the real novelty lay less in the stainless-steel equipment, which resembled breweries and enzyme plants, and more in the biology upstream. Vow spent significant time validating cell lines, assessing whether new allergens could be produced and understanding how the cells were digested. She argued strongly for a risk-based approach to testing, rather than simply overwhelming regulators with data.

“More data is not safer food,” she said. Instead of providing entire proteomic datasets, Vow preferred to work with allergen specialists or other domain experts to design studies that answered specific safety questions. She also cautioned against applying pharmaceutical testing regimes wholesale to food, noting that this had cost some companies dearly while failing to focus on genuine consumption risks.

On transparency, McCartney acknowledged that early in cultured meat’s development, companies tended to treat almost everything as intellectual property, which had made it difficult for academics and regulators to assess the category. She said Vow now distinguished carefully between its “crown jewels” and the media components and processes that were already widely known. Sharing more of the latter, she argued, would help regulators understand norms, allow laboratories to validate methods and build the scientific base that underpinned consumer trust.

Looking to the future, Santiago pointed to robotics and automation as powerful tools for reducing contamination risk, particularly by limiting human presence in controlled areas. Technologies that already existed in other sectors, he suggested, could soon make environmental monitoring more predictive and less labor-intensive.

In their closing reflections, McCartney, Søndergaard, Powell-Price and Santiago all returned to the same core message: transparency, robust certification, collaboration and education were the foundations of trust in novel foods. Companies that “did it right from the start”, as Powell-Price put it, would be better placed to avoid painful recalls and to convince regulators, customers and the wider public that sustainable foods were every bit as safe as their conventional counterparts.

The full discussion, including practical detail on environmental monitoring programs, regulatory strategy and risk assessment for novel proteins, is now available to watch on demand via Protein Production Technology International for those who registered for access.

If you have any questions or would like to get in touch with us, please email info@futureofproteinproduction.com