Vienna researcher says cutting meat consumption is one of the simplest climate actions

Eating less meat was one of the simplest and most effective ways for individuals to reduce their climate impact, according to Laura Maria Wallnöfer, a researcher in sustainable consumption behavior at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna. Speaking on the sidelines of the COP30 climate summit in Belém, she said even small reductions could make a meaningful difference. “It’s not about everyone becoming vegetarians. It’s enough if everyone simply reduces their meat consumption a little,” she said.

Wallnöfer attended COP30 as an observer for the Climate Change Center Austria and focused her research on how individual decisions shape climate outcomes. She emphasized that personal consumption choices, especially around food, offered more influence than many people realized. This was particularly relevant in Austria, where meat consumption had climbed to 58kg per person in the previous year, an increase of 0.4kg, according to Statistics Austria. The figure remained well above the levels recommended by the Agency for Health and Food Safety.

Nearly 10kg of that annual total came from beef and veal, which she noted carried especially high climate impacts. According to AGES, about one-third of global methane emissions originated from livestock farming. Methane is produced during digestion and enters the atmosphere through cow burps while ruminating. “About one-third of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions are attributable to food production and resulting dietary patterns,” AGES stated.

Wallnöfer said food choices were more flexible and affordable to change than other high-emission areas. While shifts in heating, housing, or transportation often required significant financial investment, adjusting diet did not. “The most important thing is the first, even very small step. Because in the best case, you serve as a role model for friends and family. This way, you can further increase the impact on the climate and thus for a good life,” she said.

She added that decisions made in wealthy countries carried influence well beyond their borders. The population of the Global North, a term for politically and economically privileged countries, had a disproportionate impact on the Global South. This was particularly visible in the case of beef, which is linked to soybean production for animal feed. “In countries like Austria, people can have an impact on deforestation in the Amazon and the Cerrado, the moist savanna in the interior of southeastern Brazil, caused by soybean cultivation as animal feed, through their daily decisions about purchasing beef,” she said.

Food waste represented another significant pressure point. Official figures showed that one million tons of food were thrown away each year in Austria, amounting to roughly €800 per household. Wallnöfer said reducing this waste, alongside seasonal and regional shopping, offered another straightforward way to cut emissions.

She also stressed the importance of considering socio-economic differences when discussing behavior change. People with higher incomes tended to have greater climate impacts, she said, which also meant they carried greater responsibility to modify their habits. “We must also conduct the debate according to status, which determines the scope of action,” she said.

Despite differences in income and lifestyle, Wallnöfer said the overall pattern in Austria was clear. Meat consumption across the population exceeded what the planet could sustainably support. “In Austria, it must be possible to meet one’s needs in a climate-friendly way,” she said.

Her comments reflected a growing focus at COP30 on the influence of food systems in global emissions. While governments continued to debate large-scale policy measures, researchers like Wallnöfer highlighted the role of day-to-day decisions in shaping climate trajectories. For her, the combination of affordability, frequency, and cumulative impact made dietary shifts one of the most powerful tools available to individuals.

In Austria, where meat consumption had increased rather than declined, Wallnöfer’s intervention underscored the gap between climate commitments and everyday behavior. With methane from livestock contributing significantly to global warming and beef production linked to deforestation in South America, what people chose to put on their plates remained tied to broader environmental challenges.

At COP30, where much of the conversation centered on national targets and global frameworks, her message was grounded in individual influence. Small reductions in meat consumption, replicated at scale, could deliver climate benefits faster than many policy reforms. For Wallnöfer, the aim was not perfection but progress, beginning with what she described as simple, achievable choices made in kitchens and supermarkets every day.

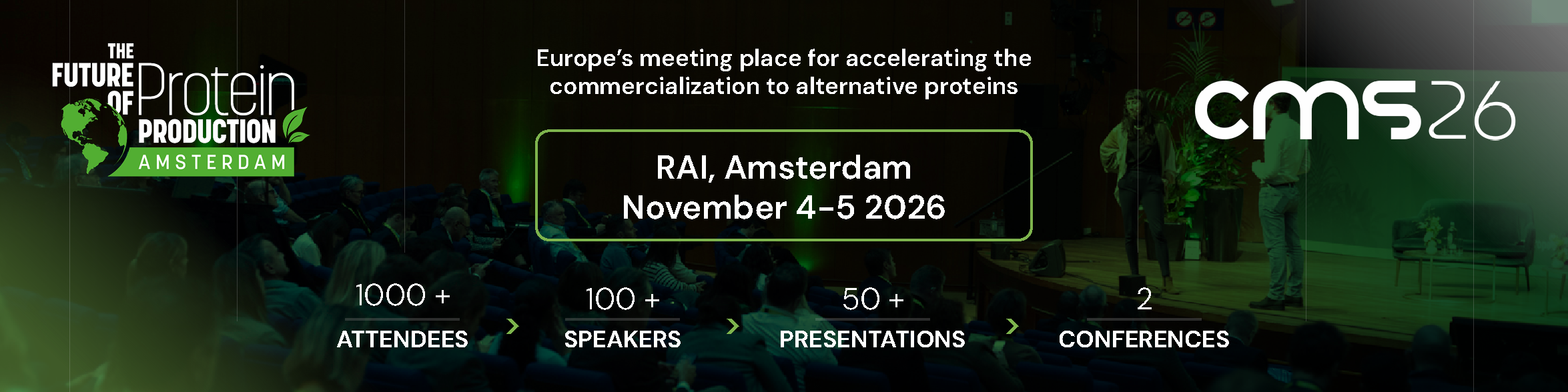

If you have any questions or would like to get in touch with us, please email info@futureofproteinproduction.com

.png)