FPP Chicago 2026 Speaker Interview: The one-day fermenter and the thousand-ton bet – The Better Meat Co.'s pragmatic play for meat that goes further

Blending fungi into meat won’t ask consumers to change how they eat. It asks manufacturers to change how they think about efficiency, cost, and scale – and Paul Shapiro is betting that’s where real transformation begins

The most consequential protein arguments right now are not being won on ideology. They are being won on yield. Not theoretical yield curves or elegant technoeconomic projections, but the blunt arithmetic of what happens when heat meets muscle.

“When you cook meat, let's say you start with 100g of meat and you're going to cook it. Most likely you're going to end up with about 70g of meat after cooking because there's a lot of yield loss when you cook.”

For Paul Shapiro, that shrink is not a culinary footnote. It is an efficiency problem embedded deep in the modern meat system, a place where value leaks out of a supply chain otherwise optimized for scale. The Better Meat Company, which Shapiro co-founded and leads, is built around a different premise: that meat can become materially more efficient without asking consumers to abandon it.

The company’s approach centers on biomass fermentation and a fungi-derived ingredient called Rhiza mycoprotein. Rather than trying to pull demand toward a new category, Shapiro focuses on modifying what already dominates plates and purchasing contracts, using the same industrial logic that governs mainstream ingredients.

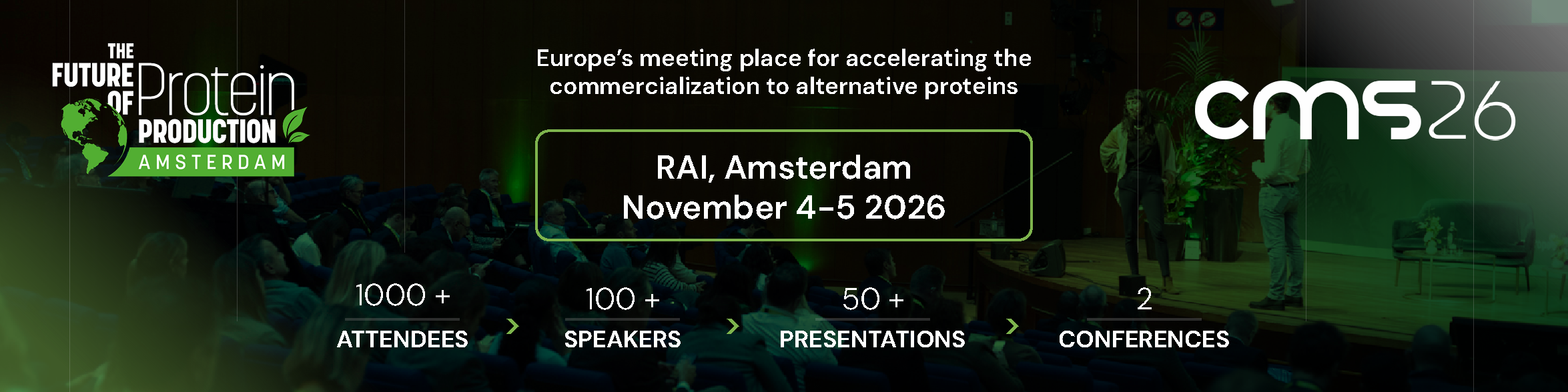

Shapiro is set to appear at The Future of Protein Production Chicago, co-located with the Cultured Meat Symposium, taking place on 24-25 February 2026 at McCormick Place in Chicago, Illinois. His outlook does not hinge on a consumer-facing brand or a rapid shift in eating habits. It hinges on whether incumbent food companies adopt inputs that quietly improve margins, stability, and performance.

A fungi protein that behaves like meat

Shapiro frames Rhiza mycoprotein less as a substitute and more as a material whose physical properties align naturally with meat processing. He speaks about performance in the language of function rather than ideology, anticipating skepticism from both plant-based and meat-first audiences.

“Rhiza is a whole food that has a naturally meat-like texture that on its own has more protein than eggs, and it's a complete protein, meaning it has all the essential amino acids. It's got more iron than beef, more zinc than beef, more potassium than bananas, more fiber than oats. It is a true superfood.”

Rather than emphasizing novelty, he focuses on subtraction. “And so you get all the things about meat that you want, the texture, the protein. You don't, though, get the things you don't want, the saturated fat, the cholesterol, the animal cruelty, and so much environmental degradation, and so on.”

That flexibility defines the company’s commercial strategy. Rhiza mycoprotein can be blended into animal meat to improve yield and nutrition, formulated into plant-based products for structure and taste, or dried into powders for sports and active nutrition. Regulatory clearance is a necessary step, but not the end goal.

“It's already generally recognized as safe by the FDA and approved by the USDA as safe and suitable for inclusion in animal meat, and we're scaling up now.”

The business model is deliberately narrow.

“You can eat it on its own, it's fine. I do it every day actually myself, and I really like it. But The Better Meat Co. is a B2B ingredients company. We are not trying to compete with meat companies. We are trying to supply meat companies to help them make better meat.”

He situates the company alongside familiar suppliers rather than challenger brands. “You can go, for example, to Cargill or ADM and buy soy protein and pea protein and wheat protein. We are offering mycoprotein as an ingredient.”

What matters, in his view, is that fungi proteins remain largely absent from that ingredient ecosystem. “There’s nobody on earth right now that is really meaningfully commercializing a B2B mycoprotein ingredient – not ADM, not Kerry, not Roquette.”

Yield as the wedge

The clearest entry point for adoption, Shapiro argues, is not consumer preference but manufacturing efficiency. “When you add Rhiza mycoprotein, instead of having 70g at the end, you're going to have about 85g at the end. So right there, that's a 15% increase in your yield.”

That gain compounds quickly when paired with input economics. “The Rhiza mycoprotein is more cost effective than the beef itself. So you get the double cost savings, and you're improving the nutritionals.”

For meat processors, the formulation logic is familiar. “When you add Rhiza mycoprotein to beef, you end up getting less saturated fat, less cholesterol, fewer calories, more fiber, but you maintain the same level of protein.”

Shapiro contrasts that with the historical cost structure of alternative proteins. “For so long, alternative proteins have been a green premium where you have to pay more in order to utilize them. In our case, they're paying less.”

The land constraint

The origins of The Better Meat Company trace back to a constraint Shapiro believes cannot be engineered away. “The reality is that the world isn't getting any bigger. Humanity's footprint on the planet is getting a lot bigger, but the planet itself is remaining stubbornly the same size.”

Population growth intensifies that pressure. “Today we have more than 8 billion humans walking the planet. And if projections are correct, within the next 25 years, there's going to be another two billion of us added.”

In his view, the issue is not whether people should eat less meat, but whether the system can meet demand without exhausting land and resources. “We're not going to be farming the moon. We're not going to be farming Mars. We have one celestial body to farm, and that's right here on Earth.”

Dietary change alone, he argues, will not arrive fast enough in regions where demand growth is steepest. “Everywhere where it's going to matter the most in the future, meat demand is going up, not down.”

The solution has to work within existing consumption patterns. “Create really stellar ingredients that we can add to meat that you can make it go much further while being even more nutritious and more cost effective.”

Why plant-based meat stalled

Shapiro’s critique of plant-based meat is grounded in market penetration rather than aspiration. “Plant-based meat today is still really in the dumps when it comes to market takeover.”

He points to a stubborn metric. “Less than one single percent of the meat industry in the USA is plant based.” His explanation follows what he calls 'the three Ps'. “You've got price. It's just a lot more expensive than meat is. You got performance. It often doesn't taste as good as meat. And you have the perception.”

He contrasts that with fermentation-based proteins by focusing on process simplicity rather than ideology. “It's cheaper than beef. It performs better than plant protein isolates. And it's not ultra-processed.”

The difference becomes clear when he describes how plant proteins are engineered into meat analogs. “You grow a field of peas, harvest them, mill them into flour, strip out the fiber, strip out the fat, concentrate the protein, then subject it to twin-screw extrusion.”

Mycoprotein follows a shorter path. “It is simply a fermentation process. No fractionation, no isolation, no extrusion.”

Time is the final variable. “Our mycoprotein can be grown in less than one single day.”

Blended meat as the mainstream product

Shapiro expects hybrid products to become commonplace rather than exceptional. “Meats that are enhanced with non-animal ingredients are going to become more and more common.”

He describes a future where meat is defined by function rather than origin. “You're going to have meat that comes from animals, meat that comes from plants, meat that comes from fungi, and hybrids thereof.”

His Burger King example illustrates the appeal. “What if the conventional Whopper was 20% mycoprotein and 80% beef? You could bring the cost down, reduce saturated fat and cholesterol, increase fiber, and keep protein the same.”

The shift requires reformulation, not reinvention.

Scale is the product

The constraint Shapiro keeps returning to is not scientific uncertainty but throughput. “We're running a demonstration scale plant out of Sacramento, California, where we could never even dream of supplying a company like Burger King.”

That limitation shapes how the company structures its next phase. Rather than rushing toward vertical integration, The Better Meat Co. spends 2025 doing the quieter work of de-risking scale: securing regulatory clearances, reducing production costs, and lining up commercial demand ahead of capacity.

By mid-2025, the company implements continuous fermentation, materially lowering unit costs and moving the process closer to industrial viability. Regulatory approvals from both the FDA and USDA follow, allowing the ingredient to be incorporated directly into animal meat products.

Commercial signals accumulate in parallel. Letters of intent are signed with large meat producers across multiple regions, covering volumes that only become meaningful once production moves well beyond pilot scale. Joint development agreements allow partners to trial formulations while committing future purchase volumes, turning the demonstration plant into a proving ground for downstream demand.

One miracle, not three

That discipline extends to how Shapiro thinks about company-building more broadly. “Our company has raised about US$43 million. That sounds like a lot, but in biotech and mycelium startups, it's not.”

Against a backdrop of heavily capitalized fermentation ventures, the company chooses focus over breadth. Shapiro frames the decision through an investor’s lens he finds persuasive. “He likes to bet on companies that only have to perform one miracle.” For The Better Meat Co, that miracle is technological: turning fungi into a functional, scalable protein ingredient. Manufacturing at scale, branding, and downstream product development are treated as separable challenges, best handled through partnerships rather than internal expansion.

Consumers do not buy processes

Despite the technical complexity behind Rhiza mycoprotein, Shapiro remains skeptical that process narratives matter much at the point of sale. “I don't think that most people think about what type of fermentation was used.”

Instead, adoption hinges on outcomes that are immediately legible. “They want to know, is this product taste good? Is it nutritious? Does it meet the needs that I have in terms of cost effectiveness?”

Hybrid products, once framed as compromise, increasingly look like a rational response to economic pressure rather than ideological positioning.

Ethics as a side effect of better technology

Shapiro is careful not to overstate the role of ethical motivation in that transition. “These are tertiary concerns for most people.”

Taste and cost continue to dominate food choices. “Most people just want something that tastes good and is cost effective.”

He grounds that belief in historical precedent. “We didn't stop using horses because we cared about horses. We stopped because cars were better.”

If the number of animals used for food declines meaningfully in the future, he suggests, it will likely be because new production methods make older ones economically unnecessary. “Make the better choice also the easier choice.”

Five years: from ingredient to infrastructure

When Shapiro looks ahead, he does not describe a single product or brand dominating shelves. He describes an ingredient category that barely exists today becoming ordinary. “There will be a robust mycoprotein ingredient industry that The Better Meat Co. is leading.”

In 2025, fungi proteins still sit at the margins of mainstream ingredient sourcing. Plant proteins and animal proteins are easy to buy at scale; mycoprotein is not. Shapiro’s ambition is to change that equation. “We're going to create that industry.”

The comparison he reaches for is not subtle. “We are going to become like Cargill as an ingredient supplier, except based on mycelial ingredients.”

Whether that ambition proves achievable will depend less on vision than on execution over the next several years. Shapiro is confident about the direction, even if the path remains demanding. “My aspirations are very high. And I do think that in five years, what I just said will be true.”

Paul Shapiro is one of more than 100 speakers taking to the stage at The Future of Protein Production/Cultured Meat Symposium on 24/25 February 2026. To join him and more than 500 other attendees, book your conference ticket today and use the code, 'PPTI10', for an extra 10% discount on the current rate. Click here

If you have any questions or would like to get in touch with us, please email info@futureofproteinproduction.com

.png)