Climate change could cut global grazing land for cattle, sheep and goats by up to half by 2100

Climate change could make large parts of the world unsuitable for cattle, sheep, and goat farming by the end of the century, according to a new study that mapped the climatic limits of grassland-based grazing systems.

The research, conducted by scientists at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, has found that between 36% and 50% of land currently suitable for grazing could lose climatic viability by 2100, depending on future emissions pathways. The findings were published today in the scientific journal PNAS.

Grassland-based grazing systems currently cover around one-third of the Earth’s land surface and represent the world’s largest agricultural production system. The study estimated that a contraction of this scale would affect more than 100 million pastoralists globally and up to 1.6 billion grazing animals.

• Researchers found that 36% to 50% of land suitable for grazing today could become climatically unviable by 2100 under different emissions scenarios.

• The study defined a safe climatic space for grazing based on temperature, rainfall, humidity, and wind conditions observed in current livestock systems.

• Africa was identified as a major hotspot, with grazing land potentially shrinking by up to 65% under high-emissions pathways.

The researchers defined what they described as a safe climatic space for cattle, sheep, and goat grazing by analyzing the environmental conditions under which existing grassland systems operate today. These systems were found to thrive within temperature ranges of -3 to 29°C, annual rainfall between 50 and 2,627 millimeters, relative humidity of 39% to 67%, and wind speeds between 1 and 6 meters per second.

According to the study, rising global temperatures are expected to shift and significantly reduce these climatic zones over the coming decades.

“Climate change will shift and significantly contract these spaces globally, leaving fewer spaces for animals to graze,” said lead author Chaohui Li, who was a researcher at PIK when the study was conducted and is now based at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center. “Importantly much of these changes will be felt in countries that already experience hunger, economic and political instability, and higher levels of gender inequity.”

The analysis showed that grazing systems are particularly vulnerable because they rely directly on environmental conditions rather than controlled inputs. As climate variables move outside historically stable ranges, traditional grazing practices face increasing pressure.

“Grassland-based grazing is highly dependent on the environment, including things like temperature, humidity, and water availability,” said coauthor Maximilian Kotz, a researcher at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center and PIK. “What we see is that climate change is going to reduce the spaces in which grazing can thrive, fundamentally challenging farming practices that have existed for centuries.”

The study identified Africa as one of the most exposed regions. Under a low-emissions scenario, African grasslands could shrink by around 16%. Under a scenario in which fossil fuel use continues to expand, the loss could reach as high as 65%.

Researchers noted that much of the continent already sits near the upper boundary of the safe climatic space identified for grazing. As temperatures rise, the zones that currently support grazing in regions such as the Ethiopian highlands, the East African Rift Valley, the Kalahari Basin, and the Congo Basin are expected to shift southward.

Because the African landmass ends at the Southern Ocean, those temperature bands would eventually move beyond the continent’s southern edge, leading to a permanent loss of suitable grazing land rather than a relocation within the region.

“This shift away from what we’re identifying as the safe climatic space really challenges the efficacy of adaptation strategies that have been used in places such as Africa in times of hardship, such as switching species or migrating herds,” said Prajal Pradhan, assistant professor at the University of Groningen, PIK researcher, and coauthor of the study. “The changes are just too big for that.”

The findings raised questions about the long-term viability of livestock-based livelihoods in regions already facing food insecurity and economic vulnerability. While adaptation measures have historically allowed pastoral communities to cope with climate variability, the researchers suggested that the scale and speed of projected changes could overwhelm those approaches.

The authors emphasized that emissions trajectories played a decisive role in determining how much grazing land would ultimately be lost. Lower-emissions pathways were associated with significantly smaller contractions of viable grazing zones, while continued expansion of fossil fuel use led to the most severe outcomes.

“Reducing emissions by rapidly moving away from fossil fuels is the best strategy we have to minimise these potentially existential damages for livestock farming,” Li said.

The study added to a growing body of research examining how climate change is reshaping the physical boundaries of food production systems, with implications for land use, rural livelihoods, and global food security over the coming decades.

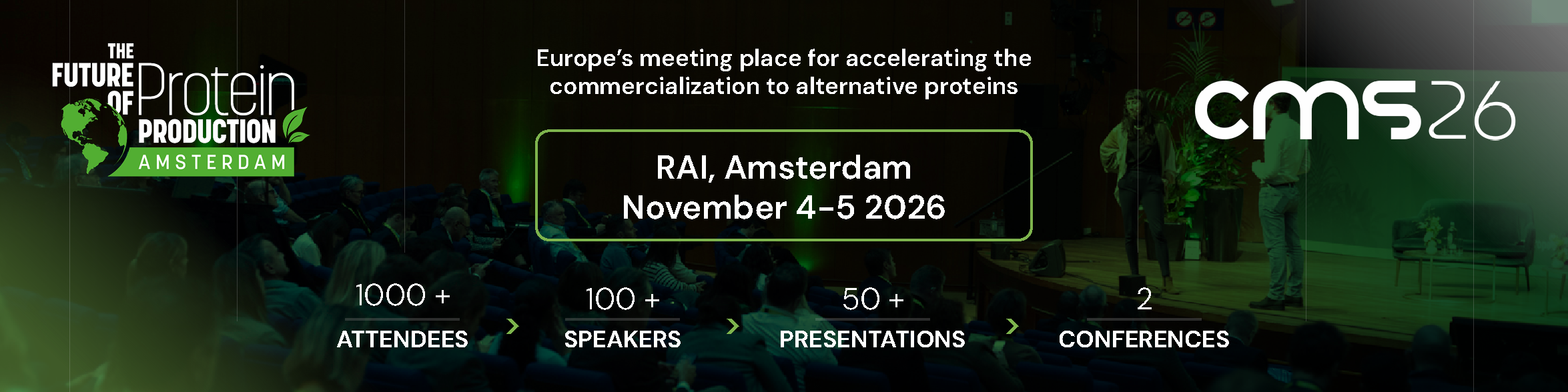

If you have any questions or would like to get in touch with us, please email info@futureofproteinproduction.com

.png)